Ryan Gosling has been a dreamboat, an anti-hero, a living doll, and now he’s achieved his final form: a bona fide movie star.

He costars with another movie star, Emily Blunt, as a pair of bantering, bickering lovebirds in the romantic action comedy The Fall Guy, a big-budget salute to unsung Hollywood stuntmen that is overlong but endearing nonetheless, specifically because of the leads.

David Leitch, director of bloody bang-bangers like Atomic Blonde and Bullet Train, recklessly steers the silly backstage story, jumping from longing glances between Gosling and Blunt to car crashes and explosions. The jokes don't always land, but plenty of punches do. There is mayhem galore! The movie is like a dopey big brother who buys beer and makes dated cultural references.

There are other actors in the cast—Hannah Waddingham, and Winston Duks smile and charm—but this is all about Gosling and Blunt flirting amongst the flames.

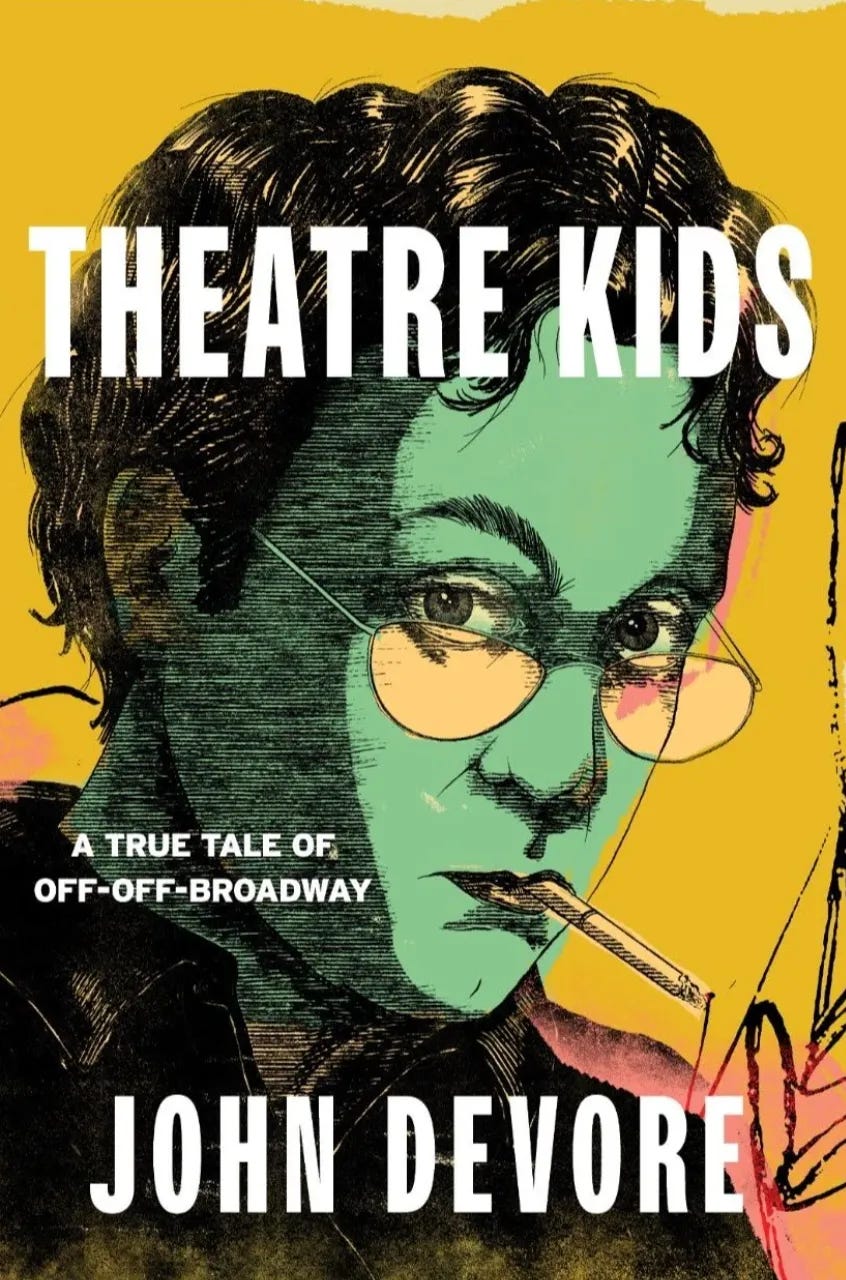

Grief, friendship, Jazz Hands. My debut memoir, Theatre Kids, comes out June 18th.

New 150 Word Review: ‘Beau Travail’ (1999)

Essay: ‘Drive’ (2011)

The sidewalks of Burbank are mostly empty, and I used to walk them when it was sunny and at night. I’d walk to Trader Joe’s and Universal City multiplex, and every weekday, I’d walk to work and then home. On the weekends, sometimes, I’d… walk. I’d walk next to trees, over freeways, and towards the mountains, which are far away.

I walked because I was sad or wanted to clear my head, and I had nothing better to do. Sometimes, I’d get so lonely that I’d walk to the 24-hour CVS and stroll the discount aisles at midnight with the other vampires.

Since the sidewalks were pedestrian-free, for the most part, I could listen to music and sing at the top of my lungs, and no one wooshing by in their cars could hear me. They also didn’t see me because, in Southern California, pedestrians are invisible.

I could belt out power ballads like Queen’s dramatic yearning Somebody To Love, and I would strain loudly to hit that one high note even if my voice gave out. This was, oh, thirteen years or so ago.

One Saturday afternoon, after walking to a bakery that made these delicious, flaky little meat pies, I decided to walk to the local Halloween store because the day was bright and 100 degrees at least. The Halloween store was windowless, cool, and full of gruesome costumes, magic tricks, and pranks. As I got ready to cross the street, I saw a man wearing a familiar silver jacket with a golden scorpion embroidered on the back.

It was the jacket Ryan Gosling wore in the mesmerizing 2011 neo-noir Drive. That movie is one of my favorites. I was in L.A. because of it. I’m serious. Drive is full of good stuff, like car chases, brutal shootouts, and a great cast of grizzled old character actors. The comedian Albert Brooks has a small part, and he plays a terrifyingly laidback villain. Carey Mulligan is in it, too, as the love interest. It’s not much of a role, but she glows, as always. Los Angeles is a character too, a radiant never-never land that's mostly pirates.

Of course, this man wasn’t Ryan Gosling, but for a moment, I got sweaty thinking, “What if it was?”

So I followed the guy. I kept my distance. If he took a left, I took a left. I wanted to know where he got that jacket. Eventually, he entered an apartment complex, and I never saw his face. I wanted to be his friend. We had a lot in common—specifically, the movie Drive.

The valley is hot and godforsaken, the roads are crowded, the winds are sharp, midnight is cold and flightless, and wild things are hiding in the quiet gloom, and it can make a person a little wild if they weren’t already that way. The air tastes like flowers and bones. I had friends in Burbank, Toluca Lake, Hollywood, and Santa Monica. But not many. All cities are lonely in different ways; New York smothers, and Los Angeles swallows. I spent much time alone that year, the beginning of my second.

I used to walk the sidewalks of Burbank because I didn’t have a car. If you don’t have a car in America, you’re either a drunk or — even worse — can’t afford one. I was sober and gainfully employed, though. I made enough money to go into debt.

I didn’t have a car because I didn’t know how to drive.

***

There are two reasons I never got my driver’s license in high school. The first, honestly, is I was lazy. My friend Fred had a van, and he’d pick me up. We’d drive around the endless suburbs of Northern Virginia for hours singing Queen’s duet with David Bowie, Under Pressure, alternating who sang who, but Fred had the better Freddie Mercury-esque falsetto.

I was lazy and knew I would never be allowed to drive the family car. We had one car, a brown 1986 Ford Mercury, and my parents would not let me get behind the wheel of their car, so Fred would pick me up, and we’d cruise around until curfew, which was 10 PM for me. I could have learned to drive, but why? Instead of going to driver’s ed, I fucked off, read comics, wrote mash notes to girls, and dreamed of moving to New York City.

The other reason I never learned to drive was that my parents were unwilling to let me use the family clunker. Even if I had gotten a license, I wouldn’t have had a car to drive. We were a one-car family for the time being. When I was nine, seven years earlier, my older sister, by ten years, got into a terrible car accident. She was thrown through the windshield and onto the highway, and the local hospital’s brand-new helicopter carried her to the emergency room.

She was in a coma for a few weeks, and my memory of the months that followed are distant, as if they were a story told to me once long ago instead of something I lived through.

I remember a few things. I remember feeling scooped out. My mouth dry. I remember seeing her in the hospital. Beeps. Snow White with two black eyes. I tried to be quiet because I thought I’d wake her, and she’d yell at me and chase me into the basement and behind the broiler, where I would eventually cry, and she’d laugh and laugh, and then my tears would also turn into laughter. Magic. Sister magic.

One night, my mother came home, and I overheard her telling my dad how my sister had spoken to her. She momentarily gained consciousness and asked for her mommy, a word she used only as a child.

My mom whispered the next part: my sister told her a nice man wanted her to go through a door with him.

She said my sister said, “Should I go with him, mommy?”

“What did you tell her?” Even when he spoke softly, my dad was loud.

“What do you think I told her?” She paused. “I said: Do not go through the door, mija. Do not go through the door.”

My mom and dad tried to muffle their tears, but I’ve never forgotten them weeping in the other room. I now know why they didn’t want me to get near the car.

When my sister finally woke up, it didn’t take long for her to start making gentle fun of me again, and I was happy to be made fun of by her. She was cool as hell.

I remember being her passenger in her new car, not so many years later, after she’d recovered. She’d remind me to buckle up, and then off we’d go, laughing.

I remember her picking me up from school, the train station, and the airport. She was always picking me up and dropping me off. I remember her driving me to eat pizza, the movies, or to visit our sick father. I remember her laughing, smoking, and singing, her fingers softly drumming on the steering wheel to rock songs on one of her mixtapes.

After our father died, she was the one I would call with questions. She was funny and smart and knew how to do adult things like paying taxes, interviewing for a job, or buying a car.

We never spoke about the accident. I thought she was fearless, immortal, and I believed that until her unexpected death at 46. Her name is Wendy. She wasn't named after Peter Pan's favorite Darling family member, but, as a boy, I thought she could fly.

I never learned to drive because I didn’t have the typical teenager’s lust for joyriding. I had better things to do, and I didn’t have a car, and besides, driving scared me. Then, as an adult, I moved to a city where I could hail taxis, and that’s why I never got my driver’s license until I was 38 years old.

This probably emotionally stunted my development as an American.

***

I was in the back of a cab on my way to LAX and a crowded redeye to JFK when I decided to move to Los Angeles from New York City if offered the job. I was in town for 36 hours for a big interview, and in those 36 hours, I went from “I can’t live in this wasteland” to “I totally can live in this wasteland.”

Many factors contributed to this transformation, but the biggest was probably Ryan Gosling. The night before the big interview, I was sitting in a hotel in Burbank, nervous and jetlagged, and I ordered the new movie Drive on pay-per-view. It was, like, $20, but carpe diem.

Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, Drive is filthy and slick—a neon demolition derby. The opening song, by French musician Kavinsky, is a sensual, hypnotic electro-synth banger. I had heard about Drive but hadn’t rushed to the theater to watch newly minted sex symbol Ryan Gosling as a Hollywood stuntman and freelance getaway driver navigating L.A.’s underworld, a scorpion amongst scorpions, all of them true to their natures.

I also ordered two room-service cheeseburgers and ate them because I was newly sober, single, and anxious.

In Drive, Gosling plays a living cemetery statue with deep, soulful, laser-beam eyes. He’s a reluctant hero with lots of feelings underneath the hood. If you stab him, he bleeds.

The movie is in love with L.A. at night, which is nothing but endless streets and lights and shadows. It’s beautiful. The darkness hides the ocean and the mountains, but the city sparkles like ice on the dance floor.

New York is the beating concrete heart of the empire, but L.A. is a bright, cloudless promise. There's hope at the edge of the world.

The plot is a freeway—it snakes lazily, forever forward. Gosling's character is perfectly happy living as an underachieving Hollywood daredevil and underworld chauffeur. He's a human ice cube until a hard-luck neighbor and her kid melt him. He tries to help her ex-con husband but ends up trying to save them both.

Gosling is a man in Drive. Like, grrr. Tough. Silent. A real American. He’s got multiple jobs. Chews a toothpick. He’s nice to children. He is good at kissing and violence. He can drive like a maniac. I sat in a king-sized bed, ate cheeseburgers, watched Gosling shift gears, put the pedal to the metal, and make wheels squeal. I resolved, sitting there, that I would move to the West Coast and drive.

I would buy a white satin jacket, pull brown leather driving gloves over my fingers, and rule Hollywood Boulevard. This was the plan. When I woke up the next morning, I was ready. The job was mine.

The interview had been with a celebrity who averted his gaze when talking to me, like an 18th-century monarch. I bored him, but everyone seemed to, and I was told I was hired right afterward. But I was told to take the night to think it over. I did and watched Drive.

The celebrity was the boss and didn’t make lowly hiring decisions; meeting him was just a courtly formality. That way, in the unlikely event that he asked who I was, they could tell him my name and that he had already met me. They could tell him the truth. It’s not that they never lied to him; it’s just that keeping track of the lies was a lot of work.

At that point in my life, I was a New Yorker. I would tell people every chance I could, even in New York City, which is nothing but New Yorkers. It was a hard lesson to learn, but I did, eventually: being a New Yorker is not a personality.

So I accepted the job. I packed my entire life into two suitcases and moved from a fourth-floor walk in Queens to a small furnished bungalow across the street from Warner Brothers Studios. I was starting over. My sister had died a year before that, and a few short months before my brother-in-law found her dead on the bathroom floor, I had quit drinking. I promised myself if I moved to L.A. I would start jogging, attend many AA meetings on beaches, get my driver’s license, and buy a car.

For a long time, I did none of those things.

***

Everyone I spoke to gave me the same advice I did not take: “Whatever you do, do not go buy a car alone.” So, like Ryan Gosling's lone wolf character in Drive, I went to a car dealership near my apartment alone to buy a car because I lived in Los Angeles.

I was alone when I stepped onto the lot, and within five minutes, an older gentleman had his arm around me and asked me how my credit was, and I told him. It was okay.

Good enough!

He immediately started showing me a few used cars. At one point, I got cold feet and told him I was just looking and what if I came back tomorrow. He said he wouldn’t be in tomorrow or the next day because he was getting “a little heart surgery.”

My face dropped when he told me that, and then he looked me in the eyes and whispered that it was important to him to know that I got the best deal possible on a lease for a used 2009 Toyota Corolla. He said I could drive a fine automobile home today and then asked me if I wanted to take one of the cars on a ride, to which I replied, “Oh no,” as if I were turning away a boring appetizer on a platter at a boring party.

“You have a license, right?”

“Yes. I do.” And I did, and it didn’t quite occur to me how important it is to take cars you will buy on a test drive. It’s an essential part of the ritual. I don’t try pants on when I go shopping, so I didn’t get why I needed to tool around with the old man, but I did and I ran a red light and hit the breaks a little too hard a couple of times, and I saw him watch me, for a brief moment, and I could read his face. I knew what he was thinking. “This guy shouldn’t be driving.”

I shouldn’t have, but it was legal. I had a driver’s license. It only took me two years to get it.

The only way to truly understand the American economy is to buy a car — a chummy process of backslapping, promises, and signatures that ends with a firm handshake over a large desk with a man who wears a gold watch. You sign a lot of papers.

I got a fair enough deal. I should have called someone at least and asked them what they thought. But my sister was the only person I wanted to call with those questions.

***

“This is the best our civilization could come up with?”

These were my first thoughts after my driving instructor bullied me into merging onto the 405. I had never driven in full-on, bumper-to-bumper traffic. I wanted to projectile vomit.

Los Angeles residents think their car horns are photon torpedoes. The first time I was fired upon, I shrieked. I wasn’t doing anything wrong; I was just trying to make a left turn. Hell is making a left turn in L.A.

My instructors ran the gamut from “cruel taskmaster” to “very recently drunk.” I tried one instructor with a Pavlov fetish who clicked a small clicker whenever I made a mistake. That taught me to fear crickets.

I hated driving—more than I thought I would. Cars go very fast, and it’s dangerous. I prefer buses, subways, and legs, and I am in the minority, especially in L.A.

The right to drive is practically a Constitutional Amendment. Love it or leave it. Jesus takes the wheel because Jesus loves to tool around.

After all, automobiles are the chariots of our dreams—the noisy, deadly, precious resource-chugging chariots of our pre-financed, previously owned dreams—dreams paved with miles of roads. Is your life a crushing disappointment? Just throw a couple of bikes on the roof of your car and go off-roading. Cruise control will set you free.

Until then, sit in traffic and scream. Don’t worry, no one will hear you or even notice because they’ll be screaming, too, inside their wooshing cars.

Admitting to hating driving in America is like admitting that apple pie is inferior to any cake, or that the national anthem should be changed to the “Na Na Na Nananana” part at the end of Hey, Jude, or that America’s foreign policy is fundamentally flawed.

But Ryan Gosling looks cool, staring in his rearview mirror and gunning the engine. I wanted a change. This would be my chance.

Eventually, slowly, I learned how to drive. (Poorly.)

***

Tim was an intern who loved Taylor Swift and Drake with equal passion. He drove me to take my first driver’s license test. I asked the office if anyone would do me that favor, and he enthusiastically volunteered.

We listened to Taylor Swift on the ride, and he insisted I listen. So I sang along to We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together.

He asked me jokingly if I had studied for the test, and I responded that I had studied as well as any 16-year-old, which wasn’t a lie. I became so crosseyed reading the driving instruction books I asked myself how a teen in the new century would study for their learner’s permit.

So, I spent a night memorizing a YouTube video of the test that some kid had secretly recorded with his phone. I knew the questions in advance and had memorized the answers.

He dropped me off at the DMV. He wasn’t the only person dropping someone off at the DMV. You can bet there were more than a couple of mothers depositing anxious teens at the doors of a mighty government institution that stood between them and the beginning of their adulthood.

In this scenario, my mother was a 22-year-old Taylor Swift fan.

I gave him ten dollars to go to 7–11 and buy whatever he wanted. Ten dollars can buy a nacho feast with money to spare. Then I walked into the DMV.

There is a reason we teach teenagers how to drive. That’s because teenagers have a casual relationship with their mortality. Honestly, there should be a cut-off date. I say that date is 30. If you haven’t learned to drive by 30, you’re probably too smart to pass the test successfully. You realize there are consequences in this life. I flunked the test.

A few weeks later, I retook it. This time, I took a cab.

“I passed?” I looked at my instructor. I was sure I had flunked again, but I couldn’t believe that the streets were full of drivers who, like me, had passed their driver’s test.

The guy who sold me my Corolla couldn’t believe it either. After the test drive, he inspected my license before escorting me to the man with the gold watch. As I drove away, he waved and told me to “drive safely,” but not in the casual way most people say it like it’s a goodbye. No. He meant it. I was to drive safely.

I drove my car home from the lot. I was honked at only once. I did not look like Ryan Gosling because I was hunched over and sweating and my stomach was upset, and I kept forgetting about my blinker. I parked the car in my garage, which took longer than it should but to my relief, there was no one to see my multiple attempts to steer myself between the two white lines.

I had to call AAA a few months later because my car wouldn’t start. I got a jumpstart, and the guy with the pickup asked me when the last time I had turned the engine over was, and I said it had been since the autumn, at least. It was the winter, I think, mudslide season. He told me I should run my car at least once a week to keep my battery from dying. Once a week, not every three months or so. I nodded and thanked him.

I did what I was told. The next week, I got in my car. I turned the key. I put my hands on the steering wheel and sat there. I did not drive it anywhere. Later, I went for a walk.

CORRECTION: a valued subscriber who shall remain nameless pointed out to me via text that David Leitch did not direct John Wick -- he co-directed it but was not credited -- so I made a few wholly tweaks to correct that error. I apologize. Thank you for your continued support.

A beautiful essay which leads me to wonder why you moved back to NYC.