Americans don’t like taking responsibility for their political realities or fantasies. British filmmaker Alex Garland exploits this truth in Civil War, his upscale shlock flick about a near future where we, the people, are killing each other, but no one is to blame. Garland comes off as a tourist poking around another nation's wounds.

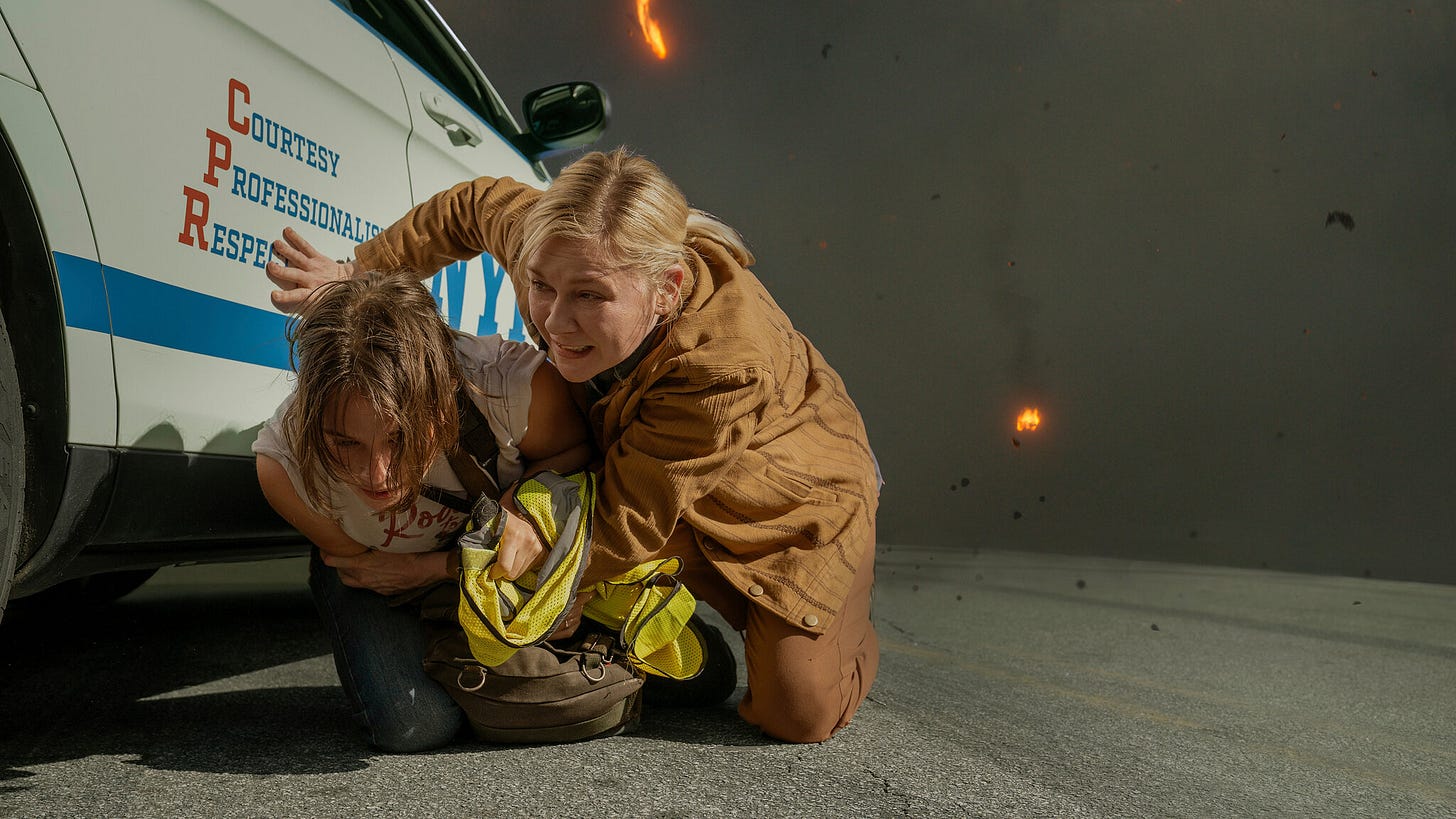

The movie is straightforward: a diverse quartet of journalists/rubberneckers hit the road to cover the fall of Washington, D.C. Led by a veteran photographer played by Kirsten Dunst, these four explore states turned red from bloodshed. The violence is ugly. However, the siege of the White House is exciting! Hollywood frequently uses war-torn banana republics as dramatic backdrops, and now it's the land of the free's turn. Fair enough. But the movie's ideological ambiguity feels like a cynical choice: Why alienate ticket buyers?

Dystopian nightmares are warnings. Civil War offers an obvious one: war is bad.

Random Rankings

Top 5 Journalism Movies

5. 'The Insider' (1999)

4. 'Shattered Glass' (2003)

3. 'Citizen Kane' (1941)

2. 'Spotlight' (2015)

1. 'All The President's Men' (1976)

Essay: ‘Gangs of New York’ (2002)

The action-packed climax of director Martin Scorcese’s 2003 historical drama Gangs of New York occurs during the infamous Civil War Draft Riots, which tore Manhattan apart.

The movie is a revenge tale that mixes fact and fiction into one legend about a baby-faced Irishman’s quest to kill his father’s murderer, the cleaver-wielding, immigrant-hating, New York dandy Bill the Butcher.

As two generations of immigrants fight to the death in the infamous Five Points slum, Scorcese dramatizes the real-life Draft Riots: mobs of white men attacking innocent Black Americans throughout New York City. Why did this happen? Because they didn’t want to be conscripted in the war between the states.

The Draft Riots were four days of violence during the summer of 1863 sparked by the Federal government’s attempts to enforce the first national draft —the Union desperately needed soldiers for a war that was proving to be costly, in both treasure and lives. The draft required white men between 20 and 45 to sign up, and the only way to get out of the draft was to pay $300 for a waiver or be a Black man.

On July 13th, the second day of the draft lottery, white men who could not afford the waiver — mostly working-class — began to riot. The mob eventually turned from looting and burning the Black community's houses, businesses, and institutions to hunting down Black men and murdering them in the streets. The riots overwhelmed law enforcement, and the US Army had to put them down. Eventually, over a hundred people would die. Because of these riots, there was a mass exodus from Manhattan by Blacks who had lived there for generations. They were not safe nor wanted.

That Scorcese used the chaos of the Draft Riots as scenery for his movie’s big finish both minimizes and elevates a historical event, most Americans don’t know about. I didn’t know about it when I first saw the movie and was quite surprised to learn about the insurrection.

Americans are taught that the North was the good guy during the Civil War and that the South fought to preserve slavery. I grew up in the South, so I received a second education from the dozens of Confederate memorials I was raised around. The melancholy statues of defeated men were meant to pull the heartstrings. The South was wronged. This is bullshit, of course. Racists live in the North, South, Midwest, and Rockies. The West Coast, too. This is not controversial. It’s certainly no secret. The opposite of bullshit is truth: Black Americans still fight for their freedoms.

In Gangs of New York, Scorcese makes this clear: New York City, the North’s wealthiest and most sophisticated metropolis, did not want to fight to free the slaves. It did not care about black men and women and their families. It just wanted to do what it does best, and that is make a buck.

***

Martin Scorcese discovered Herbert Asbury’s 1927 book The Gangs Of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld and spent the next two decades trying to adapt it into a movie. The book tells the story of an anarchic city ruled by the strong and merciless. A New York City populated by colorful barbarians, ruthless political bosses, and charismatic criminals.

Eventually, Scorcese made the movie he wanted, and it was a big Hollywood production. It makes sense why it was such an uphill battle: Americans are a cheerful bunch who want to be told good news even when the nation rots from the inside out. They don’t want to be told our republic is mostly marketing or that our ancestors were brutes and swindlers.

George Washington said some nice things, but America was built by greedy charlatans who waved hello with one hand while picking pockets with the other.

I guess it’s a minor miracle Scorcese got as much money as he did to tell a story that no one wanted to hear, especially a few years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It took some courage to challenge moviegoers in full flag-waving patriot mode.

Gangs of New York ended up a big-budget misfire featuring a confused and timid performance from DiCaprio but a confident and immortal performance from Day-Lewis. Critics didn’t love it, and while the movie made money, it was by no means a box-office smash. I have always considered it a movie best remembered for its period production values and the character of Bill the Butcher, but now I understand that Martin Scorcese was desperately trying to say something about America.

Gangs of New York isn’t a crime story. It’s a history lesson, and the lesson is this: America was founded with beautiful, flowery words, but the country was midwifed by violence. The history of the United States is the story of one long street fight between political parties and classes and races. The country was bloody, to begin with, and blood has flowed ever since.

This wasn’t my opinion when I first saw the movie, but it is now that I’ve rewatched it. The filmmakers wanted viewers to reexamine their modern world through the magnifying lens of Gangs of New York.

First and foremost is the idea that there isn’t as much emotional distance between then and now. I think it is quite common to think modern America is more civilized than it once was, and while that is true, Americans still kill each other daily. Americans kill each other every day. We do it for money, for sport, for kicks. The police kneel on the necks of the less powerful and then kneel in reverence before the powerful.

God bless America, the land where immigrants fight other immigrants while people of color run for their lives.

Gangs of New York also serves up some timely commentary about law enforcement. In the movie, we meet John C. Reilly’s Happy Jack Mulraney early, when he’s a member of an immigrant gang locked in a mortal battle with a gang of ‘natives,’ real Americans whose parents or grandparents likely immigrated to America shortly after she became a sovereign nation. Years later, we catch up with Happy Jack, a police officer. His primary job seems to be stealing from the poor and protecting the rich. Happy Jack transformed from goon to muscle with a shiny badge and a uniform paid for by taxpayers.

The line between lawlessness and law enforcement is a thin one.

There was a moment during the Draft Riots before the crowds decided to turn on Black people when the mob made sure to kick in the doors of the wealthy, too. In one brief scene, a robber baron is seen emptying an expensive rifle into an invading horde before being overrun. There aren’t any police to defend their mansions, but eventually, there will be, and they’ll be armed to the teeth.

***

Americans are raised to think of themselves as individualists. Nonconformists. E pluribus unum and all that jazz. The nation is built on fables about strong, silent men following their destinies. From cowboys to captains of industry, we want to be told we can do it on our own, with the help of a little talent, hard work, and, yes, luck. But Gangs of New York slyly mock these myths.

The best way to make it in America is to stab someone in the back. If that doesn’t work, join a mob and take your pick.

The characters in Gangs of New York can’t survive the dog-eat-dog capitalism of mid-19th Century New York alone. There is safety in numbers, after all. To be an American is to ask yourself ‘what gang am I a part of?” America is an endless turf war, and you’re sorted into one gang or another whether you like it or not. Political parties divide us. Businesses decide who we are. The media shouts about red states and blue. The internet begs strangers to fight strangers about fantasy-adventure movies.

And then there’s race. White people are the largest gang, of course. But they’re a gang that’s aging and shrinking. Loud, furious, violent. You are familiar with their leader. White men love him. He earned their affection, taunting Americans who are different from them in any way, and he's never looked back.

I am prone to romanticizing our republic, middle-age will do that to you, but I can’t ignore the little voice inside me that knows better: America is a collection of tribes — ancient and new — at war with each other because they don’t know what else to do. Sometimes it’s to compete for resources, but sometimes it’s just because they’re bored.

This country has always existed in a state of conflict—twelve score and eight years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation conceived in chaos—a perpetual civil war that, at best, simmers like a pot of human chili on the stove in our collective imaginations and, at worst, boils over with blood onto fields and streets.

The ending of Gangs of New York features an especially forgettable U2 song, even by U2’s standards. But as this dad rock anthem plays, we watch the famous New York skyline grow towards the stars over 140 years, swallowing a small cemetery where immigrants and anti-immigrants were once buried side by side, and with it, any memory of New York’s cutthroat past.

The nation can forget where it comes from, but it can’t escape it.

I mildly disliked Civil War for different reasons. It all felt so manufactured and distant. I will give “Shattered Glass” a shout out too! It’s so good and underrated.

Going to watch ‘The Gangs of New York’ again with your perspective analysis.

I’ll watch ‘Civil War’ when I don’t have to pay for it.

But the name and the topic made me wonder if there was any Government money behind it because people almost expect it to happen ever since Obama was elected. They HAVE done it before. Maybe if it looks horrible people won’t WANT it to happen.

I don’t like to just comment here. I with your substack was like a book club, but about movies, and you and your subscribers all joined in a discussion.

My country cousin has been collecting arms since 9/11 and I think he has enough to arm the small town of Vevay, Indiana. Thought shalt not take our town!