Essay: There is a xenomorph inside every one of us

In space, no one can hear you sigh

Visionary psychoanalyst and champion cocaine fiend Sigmund Freud explored the idea of the “death drive,” or Todestrieb in German, the impulse humans have to obliterate themselves, in his 1920 book Beyond the Pleasure Principle. I learned this in Psychology 101, a required class I often attended while high on marijuana or Robitussin (but never, ever cocaine, because it was expensive).

According to Freud, people, average everyday people, are mesmerized by the comforting promise of annihilation as much as they are drawn to life-affirming pleasure. The only foolproof way to avoid the pain of existence is to cease existing.

I have flirted with this urge. Who hasn’t? I’ve stared out the windows of office towers and wondered, “What if I jumped?” I’ve pondered the same question standing on subway platforms. I think, perhaps, so much of human achievement originates from the death drive. It's likely the only reason we know that certain berries are poisonous is because one of our ancestors asked, “What is this?”

And were I ever to encounter an alien egg, or the ovomorph, the first stage in the lifecycle of the lethal extraterrestrials from the movie Alien, I would probably watch, very intensely, as its strange, wet lips opened to reveal a tangle of tentacles and legs, a facehugger, a spider-like parasite that is the primary sex organ of the aliens that impregnates the host. I would lean in, unblinking, and wonder aloud, “What is this?”

I would not run, although that would be the best survival strategy. Run and nuke the egg from orbit.

Forget the philosophers. Sometimes, when you gaze into the abyss, the abyss spits a tendriled thing at you, and that tentacled thing forces a reproductive proboscis down your throat as you struggle for your life, gagging on the sperm-like eel pumped into your thoracic cavity.

It would not be fun, but at least I’d have a purpose.

***

The sci-fi horror Alien is a nearly perfect standalone monster movie set in a massive spaceship/haunted house. Alien never needed a sequel, or a prequel, and there have been eight of those, including a recent big-budget television series, since its release in 1979. Most of them are fun and diverting, but none of them live up to director Ridley Scott’s shocking, paranoid, anti-corporate original.

The franchise has proven remarkably sturdy, partly because the late German artist H.R. Giger's nightmarish design of the alien, also known to connoisseurs as the Xenomorph, is so spectacularly unique, a biomechanical Grendel with a phallic skull, two sets of vicious teeth, and a reptile's agility. Giger's Xenomorph is beautiful, too, slithery, slimy, and shiny.

The strongest Alien movies star Sigourney Weaver as Ripley, whose character is a no-nonsense twist on horror's final girls. Ripley is just a woman working for a paycheck who learns, too late, that she and her colleagues are merely bait for a superior life form and living vessels for its progeny. Scott, with help from a taciturn and formidable actor like Weaver, turns Ripley from a lone survivor into an action hero, a role once exclusively reserved for men.

But, hear me out: it is unlikely that I’ll ever find myself waking up in a cryopod en route to a faraway planet. Were that to happen, I would be dead within ten minutes of first contact with a hostile alien race. I don't think I'd be able to help myself. Alien eggs? I don’t even think I’d look for a stick; I’d poke the things with a gloveless finger.

This is Freud’s point. Some of us are Ripley, and some of us will always ask, “What is this?”

***

The charms of Alien are simple.

Visually, the Xenomorph is never dull: the acidic blood, the grasping claws, the long, skeletal tail whipping back and forth. The android with milk-for-blood is chilling because he’s a corporate crony working for bosses who lust after new weapons and profits. I have worked with that guy before, the office narc.

But, ultimately, a good Alien movie needs to do two things.

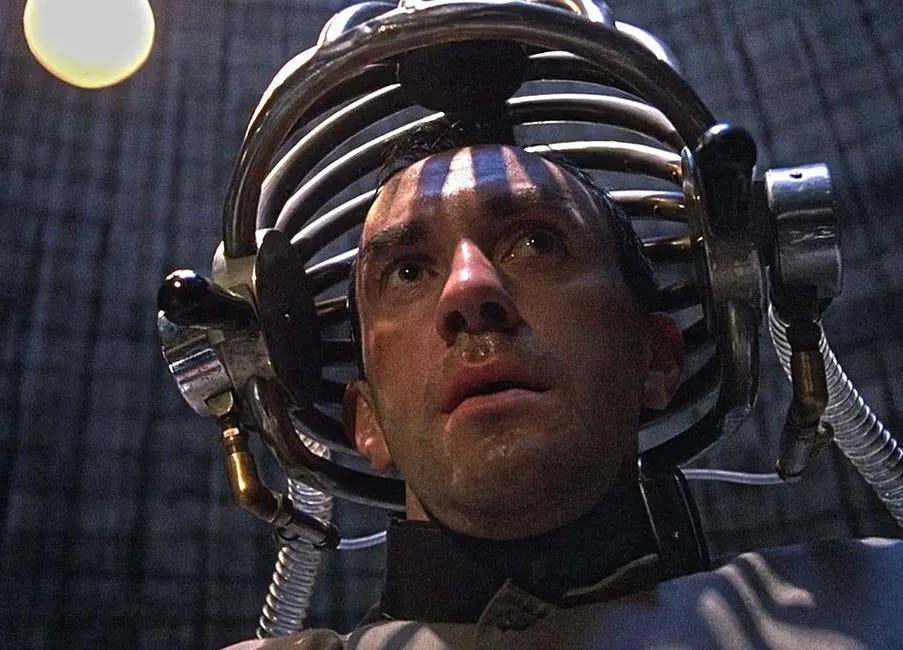

First, at some point, a larval alien must burst out of the chest of a human being in a splatter of blood; every Xenomorph is born to the sound of screams.

The other important element in any Alien movie or series is that the Xenomorph must be leered at, objectified. Each Xenomorph is an angel of death, deserving of awe.

I have distinct memories of that moment being described to my parents, who, like millions of Americans, went to see Alien in a theater, half-expecting to see a playful, special-effect-stuffed space fantasy, and instead were treated to a cosmic Grand Guignol.

Alien is a sleek, merciless meditation on primal and modern fears: sex, the wrath of God, and the cruelty of humans. Scott is both respectful of 70s cinema and popular genre conventions, and Alien, his second feature film, successfully weaves gritty New Hollywood realism with post-Star Wars special effects and grindhouse gore. The result is a spaceship that’s a haunted house.

I have thought about Alien over the course of my life. I had food poisoning once; rancid pork was the likely culprit, but as my hot, sweaty body melted into the cold linoleum of my bathroom floor, I wondered, “Is there something inside me that wants to get out?”

Then there was my first layoff. I was vulnerable to the whims of invisible managers at that job, as well as in all my subsequent jobs. I can think of no better portrayal of corporate horror than the poor crew of the Nostromo, sent to their deaths by executives and bean counters.

But the darkest, most fearsome thing Alien explores, like a scalpel searching flesh for tumors, is the fear that humans have no real purpose — other than making money and betraying each other for money and, maybe, power — and that we'd all be better used as incubating meat socks for Xenomorphs, an elegant species that stays true to their nature.

When I watch Alien now, I'm not terrified by silver teeth shining in shadowy tunnels or swarms of aliens tearing me apart with their giant claws. I'm scared of what I'd do if I were a crew member on the Nostromo. I might feel compelled, driven, to open my arms, and my mouth, and welcome the worm.

I think the new Alien: Earth series totally understands the kind of human redundancy you're pointing out here. I'm having problems with the show, but it has some magnificently bleak SF ideas, like maybe mankind has done its bit and it's time for the androids and slithery alien critters to become our children and replace us.

Loved this. Terse and taut, like the movie it (mainly) describes.