There are always exceptions to the rule, and The First Omen is one of those, a suffocating and inventive prequel to director Richard Donner's late-70s Satanic panic banger. The year? 1971. The vibes? Gritty, chaotic, disco-y.

This is director Arkasha Stevenson's debut feature, and she knows good horror isn't about jump scares, jugular spurts, or swampy atmospherics. (Those help.) No, good horror smuggles in truths between screams.

Nell Tiger Free's wannabe nun Margaret is fragile and naive at first. She quickly learns the unspeakable truth: her body is not hers. A conspiracy of holier-than-thous have a plan to save the Catholic Church. Step one: impregnate a woman with the antichrist. Step two: TBD. Ralph Ineson pops as a good priest (there are a few), Irish, and forlorn. Charles Dance smiles. Stevenson turns frowns upside down—and it’s terrifying. Everyone grins... even as they burn or bleed or birth the infernal one.

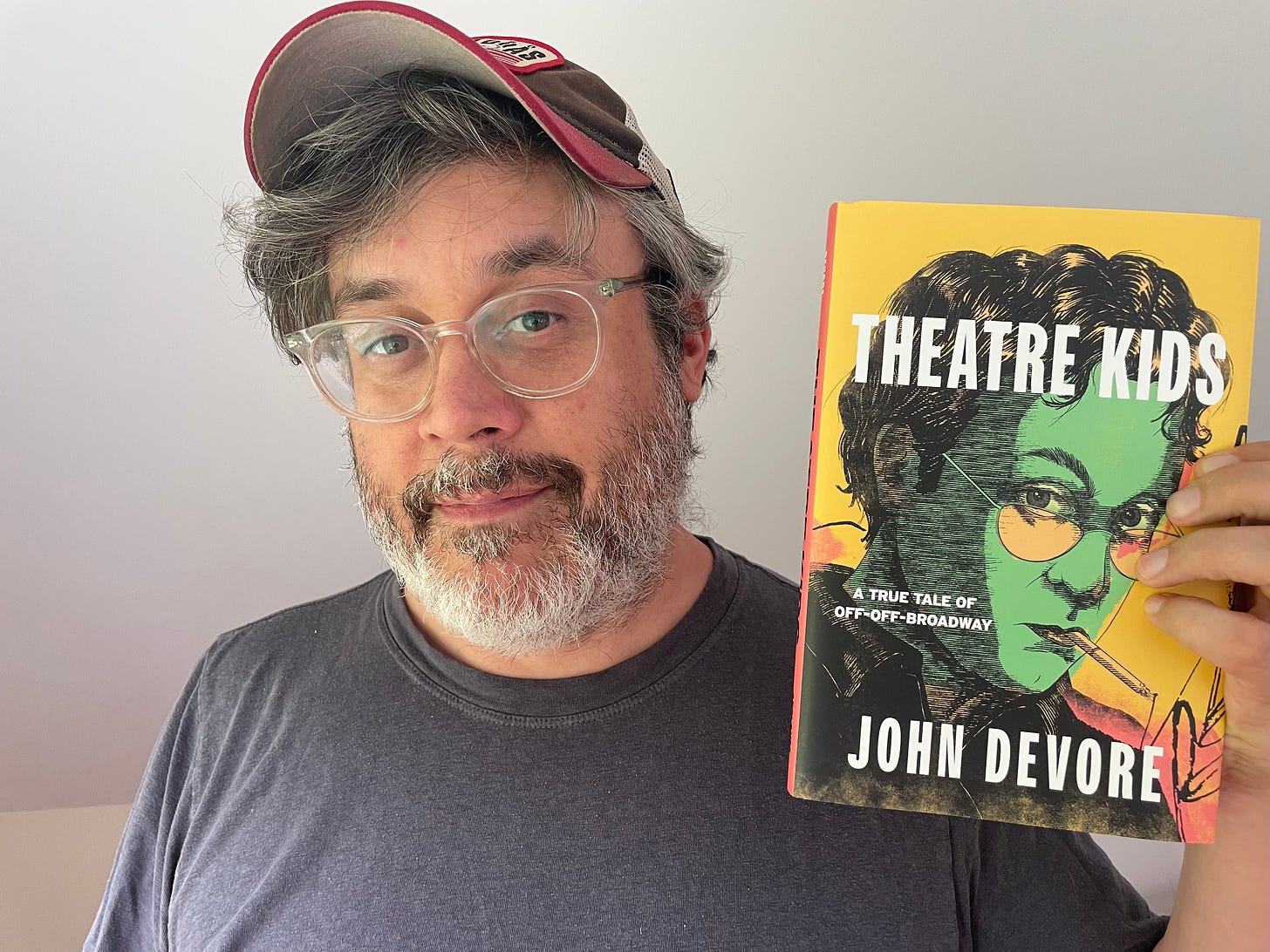

This Newsletter Is Sponsored By: ‘Theatre Kids’ by John DeVore

My debut memoir is a funny/sad, all-true story about lovable weirdos, flip phones, and performance art. You can preorder it here

Essay: “The Omen” (1976)

The 1970s was a chaotic decade, but they were also simpler years in many ways. Things were more black and white back then, except when they weren’t.

The Cold War divided the world into the freedom-loving West and the evil Soviet Union. President Nixon was corrupt, and he resigned. The two newspaper reporters who bravely exposed him were called truth-tellers. There were honest cops and crooked cops, rock music and disco, hippies and punks. The country’s mood swung between despair and hope. New York City was a crime-ridden hellhole, and in Northern California, new technologies were being invented and new companies founded. It was a time of intense spirituality and New Age fads, not to mention drugs and godless hedonism.

In the movies, the villains were clear-cut: a man-eating shark, an alien with acid blood, a killer wearing a human skin mask, and a tall, shiny space knight in black armor with a laser sword. There was no ambiguity. The bad guys were bad, and some weren’t even human.

And then there was Satan, who was the featured bad guy in easily a half-dozen flicks, including 1973’s The Exorcist, director William Friedkin’s blockbuster adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s bestseller about a little girl who becomes possessed by the Devil, and the heroic Catholic priests who try to cast him out.

The ’70s were a new Golden Age of films created by a younger generation inspired by Japanese and French directors and America’s rich cinematic tradition. These writers, directors, and actors brought gritty, realistic stories to the big screen, turning beloved genres inside out to fulfill their visions.

The Exorcist is one of the best movies of that era, a horror movie about faith that is still disturbing today. Linda Blair’s Regan's possession is horrifying and cruel, and the voice of Satan is taunting and profane. As the priests, Jason Miller and Max Von Sydow are frail humans standing up to bottomless, eternal hate. It is The Godfather of horror movies the way The Godfather is The Godfather of gangster movies.

Another movie that praises Satan is Roman Polanski’s 1968 supernatural drama Rosemary’s Baby, a subtle body horror tale about poor Mia Farrow’s character, a woman unknowingly knocked up by Lucifer. This movie’s influence still reverberates throughout the culture.

These two films, both box office and critical hits, really spoke to a truth about America almost fifty years ago: America feared unspeakable, faceless evils like Satan. The ’70s were chock full of knock-off Satan movies, from 1971’s The Brotherhood of Satan to The Mephisto Waltz from that same year. In 1974, a Rosemary Baby knockoff called Beyond The Door was a smash, inspiring a terrible sequel a few years later.

Most of the movies in the genre were garbage, but 1971’s Blood on Satan’s Claw is worth a peep if you haven’t seen it. It’s about demonic possession in 17th-century England and has strong The Wicker Man vibes.

And then there’s 1976’s The Omen, which is neither as celebrated as The Exorcist or Rosemary’s Baby but was better than any other movie about Mephistopheles from that period. It is a taut paranormal thriller with some truly memorable moments of graphic violence, and it’s about, you guessed it, everyone’s favorite fallen angel.

It was obvious, even back then, that America was capable of great and terrible acts of evil overseas and at home, but the movies that gave the U.S. nightmares were about inhuman forces stealing the souls of little kids or eating swimmers in the ocean or stalking teens through suburbia with giant knives. There was good, and there was evil—simple pimple.

This cultural obsession with Satan would spill over in the 80s, too, infecting parents with a fanatical religious paranoia that their children were being manipulated by God’s #1 enemy, a man with a red face and horns, and this hysteria ruined heavy metal music and role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons for many a kid, including yours truly.

The devil doesn’t make anyone do anything. He doesn’t exist. Humans are cruel because humans are cruel. We don’t need infernal help murdering each other. But if he did exist, I bet the devil would spend his days scrolling social media and nodding approvingly.

***

Six. Yes. I must have been six years old when my sister first saw The Omen on VHS. This was, maybe, 1980. I was not allowed to see it, but I remember her tickling me afterward, holding me down, and checking the crown of my head for a specific birthmark: three sixes.

“I need to make sure you’re not the son of Satan!”

My sister was ten years older than me, and I thought she was a fearsome goddess. Tall and powerful. She somehow knew when I was lying and would frequently demonstrate her super strength, effortlessly opening all the most important jars: strawberry jelly, marshmallow fluff, peanut butter.

For a few weeks after The Omen, she would randomly probe my noggin for evidence that I was not related to her, and I’d scream and cry and secretly wonder if she was right.

In The Omen, a powerful American diplomat can’t quite break it to his wife that their newborn did not survive childbirth and, instead, secretly adopts an orphan and tells her it’s hers. This is a terrible decision because it turns out he’s the spawn of Satan, and this is confirmed by checking the crown of his head for three sixes, the mark of the beast.

My sister wanted to make sure I, too, wasn’t the son of Satan, which would have made sense, at least from her perspective. But, alas, I did not bear the mark of the beast; I was simply Wendy DeVore’s little brother, annoying but worshipful.

I loved my sister, and she loved me, but every so often, for years to come, she would jokingly inspect my head for evidence that I was, actually, the Antichrist. Ha, ha, ha. Good one.

To be six is to believe in the binaries adults teach you. The world is ordered into right and wrong, naughty and nice, beauty and beast. I once discovered my sister’s old Barbie dolls and was discouraged from playing with them because boys play with Star Wars action figures. Most of all, I believed in angels with their wings and halos and in goateed devils lurking in the shadows.

The Catholic Mass, to a little kid, is unbelievably boring and, at the same time, strange and intense, the costumes and incense and bells and, depending on the church, a statue of a nearly naked man nailed to a cross, his face twisted in agony, hanging from the wall. I would sometimes fall asleep during the service only to wake up to an old man wearing fantastical robes talking about Jesus and Satan.

This world was divided into pure good and pure evil, and the thought that I could be evil kept me awake at night. Does Jesus know? Santa? And then I’d get philosophical: what exactly is evil?

At that moment in my life, if you had asked me to explain the concept, I would have responded that evil is telling lies, being mean, hitting someone, or stealing, which I was exceptionally good at, especially when it came to stealing Little Debbie oatmeal pies from shelves that would have terrified five-year-old John. I was a chubby cat burglar.

The following year, I would receive my first communion, an important benchmark in the life of a Catholic or, more to the point, the life of my Catholic mother. My father, the open-minded son of a Baptist preacher, was serene about it all; he just wanted me to have a spiritual life, one way or another. In the following years, I would learn about sin and wickedness and true-life horrors, but until then, the devil was the little voice that would whisper, “Use the kitchen chair to reach those oatmeal pies” in my ear.

I didn’t even picture him traditionally, with horns and goat’s hooves for feet.

There was a popular one-panel comic strip in the newspaper back in the day when the Sunday edition published pages and pages of colorful comic strips. The series was called Family Circus and followed the misadventures of a suburban family of six. Every week, there was a cartoon and a caption, and the jokes were usually cute little moments starring pint-sized Billy, Dolly, Jeffy, and baby P.J.

It was one of my favorite comic strips as a little boy because it was about little boys (and Dolly, of course.) I liked Peanuts, but it was sometimes too melancholy for me. I was a natural-born sad boy. Eventually, I would learn to love sad old Charlie Brown, but it would take a while.

My favorite character in Family Circus was the imaginary ‘Not Me,’ who the kids always blamed for their mischief. ‘Not Me’ resembled a translucent ghost who wore the words “Not Me” on his chest and a mischievous look on his face.

Who stomped mud through the house? Not me! Who threw the baseball through the window? Not me! The joke, repeated for years, was that the children blamed this little invisible imp, Not Me.

Not Me reminded me of Satan, a troublemaker and co-conspirator. I don’t know why that box of Little Debbies is empty, Mom. Not me!

And then, one night, my sister told me she had to make sure I wasn’t related to Satan. She had just seen the movie The Omen, and the little brown-haired boy’s daddy was Satan, and he was going to bring about the end of the world and needed to be killed.

My old man caught me in a white lie a few years later. He told me the Lord and the Devil were too busy to bother with me and that I was solely responsible for my words and actions. He grounded me to hammer home his point: To grow up is to own your choices. Dad was religious but also an existentialist.

***

I can’t think of two movies that are more different than The Omen and 1978’s Superman: The Movie, starring handsome and earnest Christopher Reeves as the Man of Steel.

Richard Donner directed both of those movies. Donner’s Superman is a grown-up fairy tale set in the filthy, dangerous New York City of the time. It’s a wonderful movie about a good man with great power who chooses, every day, to live like a man and not a god. I’ve seen that movie many times, but it wasn’t until recently that I saw The Omen, decades after my sister’s casual inquisition.

She passed away in 2011, and I thought about her while watching the movie. I miss her laugh, her constant insinuations that we were not really related, and her assurances that she loved me anyway.

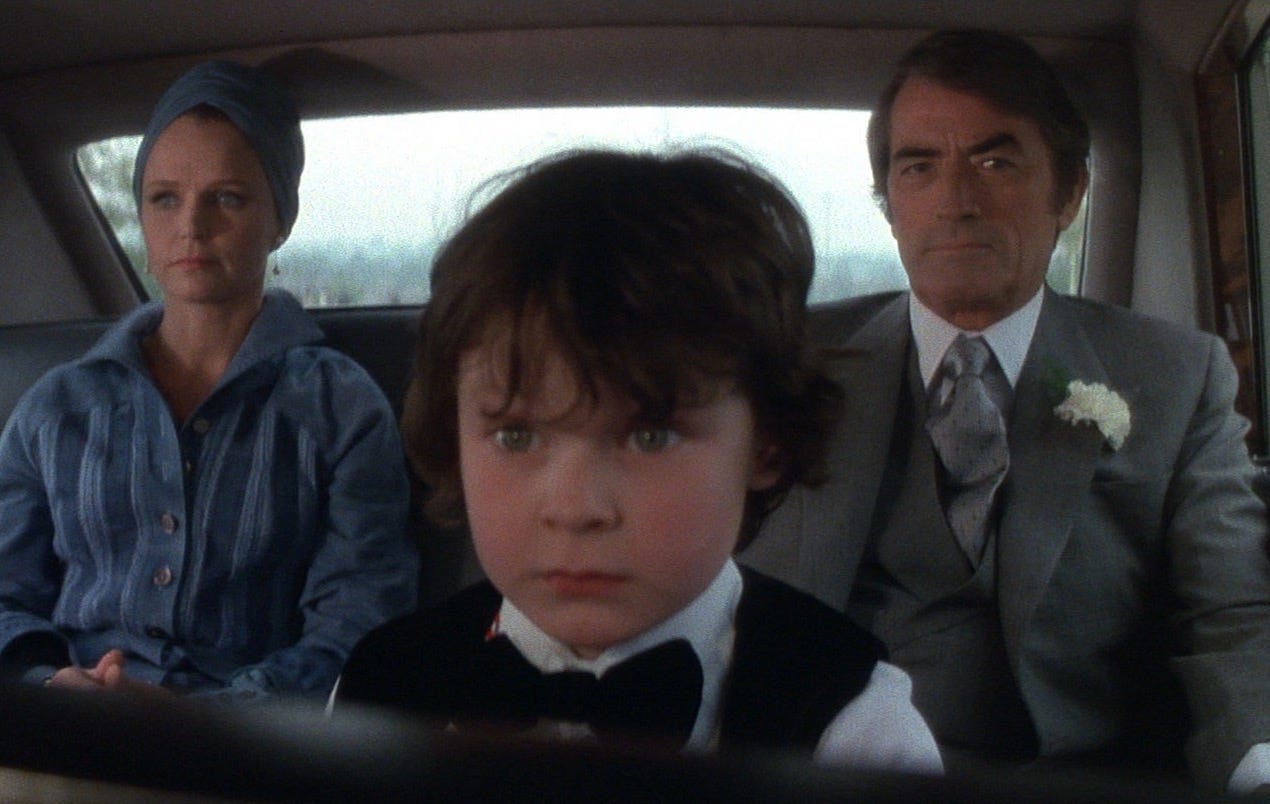

I was surprised that Donner was capable of shooting shocking scenes of violence. He was quite good at it. The Omen would have been another knockoff of Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist were it not for Donner’s macabre creativity and discipline, as well as fading superstar Gregory Peck giving a brilliant, dignified late-career performance as a man who screws up big time. The movie also stars Lee Remick as the wife of Peck’s character, a woman who is the victim of a terrible switcheroo. Her character is thankless, but she gets a pretty cool death scene.

Peck gets to thunder and fret and growl and makes a meal out of his role, but all Remick gets to do is look shocked a couple of times. She was a great actor, though, and I’ll always remember her in the timeless 1957 political satire A Face In The Crowd, a movie about America’s weakness for bullshit artists.

As the (secretly) adopted son of Peck and Remick’s grateful parents, Harvey Spencer Stephens gives one of the greatest little kid performances ever. Even at the tender age of six, Stephens instinctually knew that kids use cuteness to get what they want, and in the case of The Omen, Damien wants to rule the world as he destroys it.

When you think of child stars, names like Shirley Temple or Ron Howard, or Macaulay Culkin come to mind, but Harvey Spencer Stephens’s sinister turn as Satan’s only begotten son should be remembered, and it’s another reason The Omen is far better than it should be.

There is a montage early in the movie of the happy family doing happy family things, but that happiness is short-lived once the bright-eyed nanny kills herself in honor of Damien and a new nanny shows up—out of the blue—a severe woman named Baylock. It turns out that she is a “disciple of Hell” who swears to Damien that she will protect him. Portrayed by Billie Whitelaw, she’s the anti-Mary Poppins.

Patrick Troughton is a remorseful maniac as Father Brennan, an ex-Satanist who we first meet selling Peck’s character on lying to his wife and who, later, recants and warns him over and over again that his bouncing baby boy is Beelzebub.

The butter-smooth David Warner is a photographer who begins to suspect Peck’s son is part of a larger conspiracy, and he’s right. Once Peck realizes he adopted the devil’s baby, he’s given no choice but to attempt to perform a 20th-trimester abortion with a set of sacramental daggers. The Omen features a surprise decapitation and a dramatic, graphic, impalement scene that is, as the French say, magnifique. Then, there’s the moment when it is revealed that Damien’s mother was a jackal. The movie never stops being bonkers after that.

The Omen isn’t as brooding as Rosemary’s Baby or as harrowing and messy as The Exorcist. Faith isn’t examined. Donner’s movie is crisp and controlled and gruesome, anchored by an actor like Peck, who becomes heavier with guilt and despair as the movie hurtles towards its bleak climax. Well, it’s not bleak if you’re Satan Junior. Spoiler alert: Damien wins.

Donner gave The Omen a rare and subtle political charge for a movie about the king of hell. There are references to modern-day Israel and America’s rising power. Peck’s character wasn’t chosen randomly: He’s the U.S. ambassador to the U.K. and, therefore, connected to the President.

The American public's faith in government was shaken in the ’70s, so the idea that the White House could fall under the spell of The Accursed’s spawn was probably welcome. He couldn’t be any worse than Nixon.

If The Omen has a message, it’s a muddled one. Don’t adopt a baby without making sure its mother is human. Same with your nanny: demand references? Check your kids for 666 birthmarks. Or, my favorite, maybe you’re a bad parent? I don’t know. But movies like The Omen are steeped in a simple — almost quaint — fear of a malevolent, otherworldly spirit that wants to torment humanity. That would be a relief, actually, were it true. It’s not.

Satan doesn’t poison this world, people do.

Great review & essay! The Omen is a favorite of mine that I didn't come to appreciate until later in life (I was only 4 when it was first released). But it holds up so well and is part of a triumvirate that remains in heavy rotation for me during Halloween, along with The Exorcist and The Witch. That's why The First Omen was such a pleasant surprise to watch. Ineson's version of Brennan was particularly on-point and did homage to Troughton without mockery. It was properly atmospheric and creepy, and makes me want to watch more of Arkasha Stevenson's work.

I have to say when it comes to chills, The Omen beats The Exorcist every time. Probably because I first saw The Omen when it was shown on TV in the UK and I was about 12 years old. And, bizarrely I'm sure it was on over the Xmas holidays and my parents didn't realise what kind of film it was. I think the title spells it out.